Dante sets the tone for this oh-so-eventful canto from the very first line. And so I say, continuing the first verse begins, anticipating the sustained pace, drama, and underlying feeling that time is of the essence, characteristic of canto 8.

So, without much by way of introduction, we find ourselves on the shore of the swamp/river Styx, circle 5, repulsive “home” to the wrathful and the sullen. Before us a tower with two flames burning at the top. So far away that the eye can barely see it is another tower, also topped by a flame, and the flames of the two towers seem to communicate with one another.

Before Virgil can give more than the vaguest possible answer as to what the deal with the fire may be, our lovely infernal guardian appears. His name is Phlegyas (once again a mythological creature) and he is the son of Ares, the Greek god of war and Chryse and famous for setting fire to Apollo’s temple in Delphi (there’s a reason why, but I won’t go into it, you can read it here)

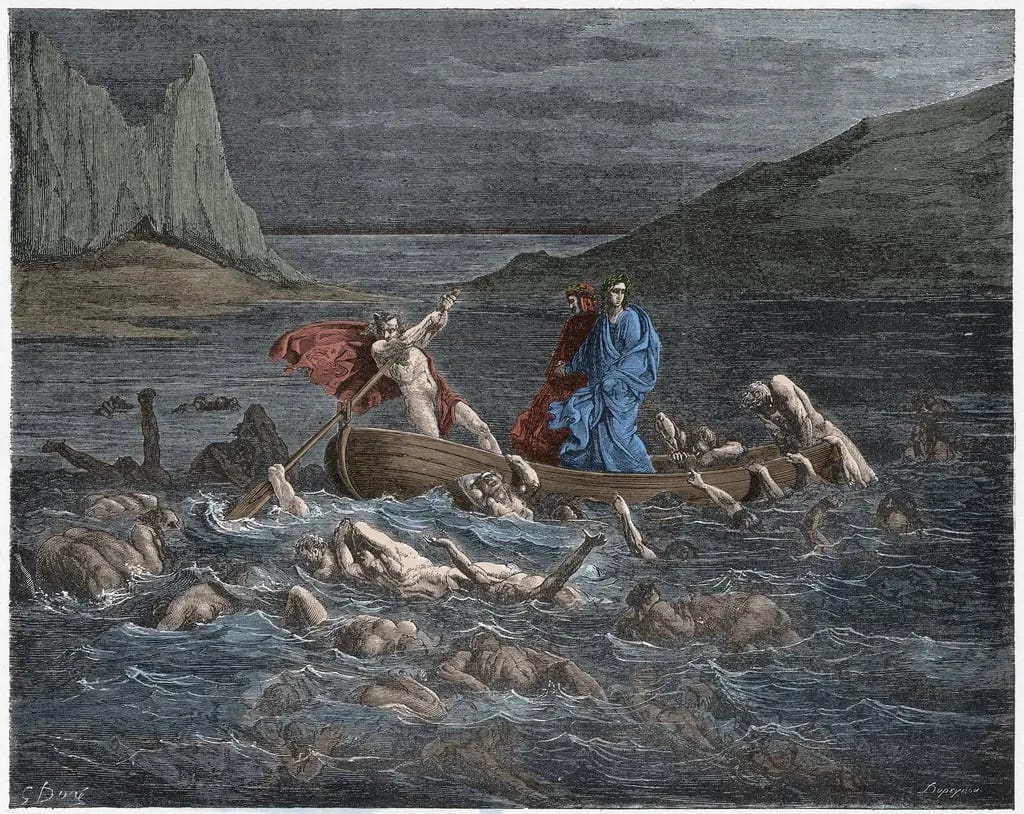

Phlegyas is abroad a small vessel in which he collects the souls of the wrathful and the melancholic and rows them onto the middle of the swamp before dropping them in for eternity. So it’s unsurprising that he’s disappointed to find out that Dante will only be hitching a ride to the other shore. I pause to give you a chance to look at the beautiful simile in verse 13, which describes the speed of Phlegyas’s appearance on his little vessel as that of an arrow shot through the air by the string of a bow. What an image. Anyway, in the spirit of this fast-paced canto, we move on.

As the boat swiftly moves over the Styx, the lifeless spectre of a sinner pops up out of nowhere and seems to be flying into Dante’s face, asking who he is and what - given that he is alive - he is doing there. But who might you be, brutishly befouled? comes Dante’s openly antagonistic reply.

I’ve often joked about Dante’s pettiness and his habit of putting his friends in heaven and his enemies in hell. But this is the first time we see it. Thus far, although Dante the narrator shows signs of judgment towards the sinners presented in the poem, Dante the pilgrim has always been compassionate. Not in this case.

The interaction between Dante and the sinner escalates quickly, with the latter ready to take physical, had it not been for Virgil’s intervention. The guide sees that the yet-to-be-named wrathful soul is about to leap at Dante and pushes him back into the swamp.

So who is this guy that Dante hates so much he’s ready to start a fight in hell?

Filippo Argenti is a historical figure, a Florentine knight belonging to the political faction of the Black Guelphs (let me remind you Dante was a White Guelph, which basically makes them natural enemies). He was known to be arrogant and a tyrant, as well as prideful. According to Boccaccio, he got the name Argenti because he had silver horseshoes made for his horse (‘argento’ means ‘silver’ in Italian).

The poem describes him as ‘superbo’, which my English text translates as ‘arrogant’, but which can also be translated as ‘prideful’. And I think this is a great example of Dante’s attention to nuance. On the one hand pride and wrath are two distinct capital sins in the Christian tradition. On the other Dante’s own organisation of Hell is very well structured. But for all his rigidity, we see here how he creates room for fluidity. Like I was saying last week, human behaviour sits on a spectrum between virtue and sin and it’s the result of a constant fluctuation between the two. But sin itself is not monolithic. By placing an arrogant man among the wrathful, Dante illustrates the complexity of human behaviour. After all, isn’t arrogance the feeling of superiority over one’s fellow human beings, and isn’t this superiority at the root of so many forms of oppression to which men have subjected other men?

So, we leave Filippo Argenti behind (his name is translated as Silver Phil in my English text and that really upsets me) and finally arrive at the shore on the other side of the Styx. The rather dramatic encounter with “Phil” is immediately forgotten, as Dante’s full attention is captivated by a great iron wall and the cries of pain coming from within: we find ourselves at the gates of the infernal city of Dis, eternal dwelling place of all the greatest sinners.

Fire is at the centre of the descriptive passages, as it has been throughout the canto, first with the flames at top of the towers, then in the figure of Phlegyas, known for having set a temple on fire, and now in the roofs of the buildings inside the city walls, which all seem to have sprung from fire.

But as all self-respecting fortress, the only way in is through a gate. A tall gate that seems to rise as far as the eye can see, framed by thousands of demons who had rained from Heaven (v.83). I love this image. The reference to rain creates an idea of an overwhelming amount of demons, so many that trying to count them would be as silly as attempting to count raindrops as they fall from the sky. But it’s also a direct reference to the Christian belief that demons were fallen angels. So the demons described are quite literally rained down from Heaven.

Another thing I love is this cliffhanger ending. We’ve seen by now how Dante likes to create suspense from one canto to the next. But never before has it ended on such a ‘life or death’ note. For the first time, Virgil can’t talk his way out or into a circle. So far, we’ve seen that a word from him was enough to placate any demon. But not now. The demons at the gates of the city of Dis don’t recognise his authority and they even suggest keeping Virgil with them and sending Dante on his way back all by himself. A more powerful figure is needed to get the poets through the gates this time. Who could that be?

Find out next week… or you know, just read ahead.

It was especially disturbing to see Dante be so vituperative toward Filippo when they’re in the circle for The Wrathful. I had been struck, previously, by how sympathetic he was being toward the punished, especially with all the crying and fainting. I’m eager to see how the rest of Inferno emotionally affects Dante, as the irony was the most poignant thing in this Canto for me.