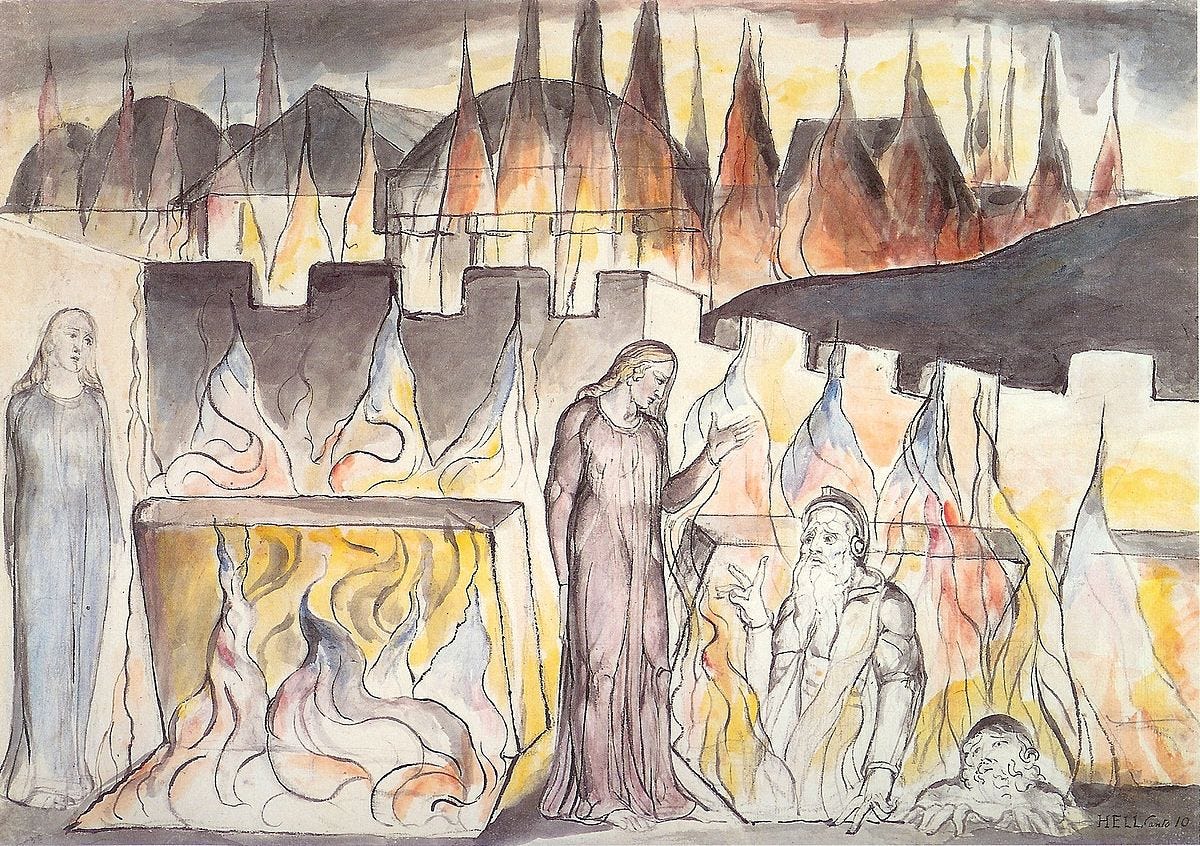

Canto 10 is a crowd-pleaser among Dante scholars. After a couple of cantos’ worth of struggle to get past the gates of Dis, Dante and Virgil are finally within the ‘safety’ of the 6th circle, which holds the souls of heretics. The verses have a fluidity to them that (at least to me) make it seem so much shorter than previous ones, and I would attribute this to their lexical elegance and linear narrative. But less about me and more about the story.

As the two poets advance towards the middle of the circle, Dante asks Virgil if he could possibly speak to someone here. As if hearing the call, a voice raises from one of the tombs and calls out to Dante:

Tuscan, you who go through the city of fire

alive and speaking as a man of worth

The speaker is Farinata, a.k.a Manente degli Uberti, a powerful Ghibelline politician of the 13th century and a fellow Florentine. He was most famously known for the part he played in the battle of Montaperti, near Siena, where the Florentine Guelphs (which Dante and his ancestors belonged to) were defeated and subsequently killed by the Tuscan Ghibellines.

Despite the numerous deaths he was probably responsible for, Dante explains Farinata’s presence among the heretics by describing him as a follower of Epicurus. It is unclear how familiar with Epicurean philosophy Farinata actually was. What is meant by “disciple of the Epicurus school” (v. 15), is that Farinata didn’t believe in the immortality of the soul, like many Tuscan intellectuals of the time, particularly of the Ghibelline faction. Epicurus was known at the time as the major “afterlife denier”, however, the Greek philosopher himself died before the supposed arrival of Christ, so the materialist metaphysics branch of his work denied the existence of Hades if anything.

But back to Farinata. Despite being political enemies, Dante is a big Farinata fanboy. From the attention to form present in this canto, to the elevated register that Farinata speaks in, to his very proud physical countenance, you can tell that this is someone that Dante admires. This is because, as we will find out in verses 91-93, after the crushing victory at Montaperti, the Ghibellines held a council at Empoli (a town west of Florence), where the majority voted in favour of dismantling the city of Florence completely and keeping the area as a small village with no political power. Farinata was the only one among them who stood up against this plan and was subsequently known as the man who saved Florence.

Despite this, the words the two men exchange remain harsh. Farinata asks Dante to introduce himself by way of his forefathers. When he explains who they were, Farinata speaks of them with the respect one reserves for worthy adversaries, despite the many times the Ghibellines had run them out of town. Annoyed, Dante observes that the Guelphs are nonetheless known for how many times they managed to return, a skill the Ghibellines have not yet mastered.

In the midst of this heated exchange, another soul rises from the tomb and recognising Dante, looks around as if searching for someone. Eventually, without feeling the need to introduce himself he asks Dante where his son is. If Dante has been allowed to walk through Hell while alive through his own merit, then surely his son must have been given the same honour.

The man in question is Cavalcante, father of Guido Cavalcanti, Dante’s contemporary and a major literary figure of the time.

Dante explains that he has not been granted this journey on account of his intellectual achievements but through divine grace from the God that Cavalcante’s son, like the father, had rejected. Had? As in he is dead? Cavalcante asks, and overcome by grief falls back into the fiery tomb without waiting for an answer.

With Cavalcante out of the picture, Farinata continues to speak as if there never was an interruption. And here comes my favourite part of the canto.

Picking up from where he left off, Farinata tells Dante that he will also soon know the weight of not being able to return. This is the second prophecy of the poem thus far (remember Ciacco?) and the first time Dante is explicitly referring to his exile from Florence (I will remind you he wrote the Comedy while living in Ravenna).

Now for my least favourite part of the canto: instead of asking him to elaborate, Dante asks him how come dead souls seem to know the future but not the present of the living???

I realise this is a pretext to have his future predicted later on by Beatrice, which Virgil anticipates at the end of the canto, saying

when once again you stand within the rays

that she, whose lovely eyes see all things, casts,

you’ll learn from her what your life’s course will be.

Yet, somehow, I still feel like I would have asked, you know?

Anyway, Dante’s irritating cliffhangers aside, the canto ends pretty uneventfully, with no mention whatsoever of what might come next. Which I suppose is a way to build expectations, too.