Trigger warning: suicide

Canto 13 opens upon a dark forest of twisted trees, a sight unlike anything Dante has ever seen before. Nothing he’s ever heard before either; as he steps into the thick of it, a wave of disembodied cries engulfs him from all sides. ‘I would explain but you won’t believe me’, says Virgil inviting Dante to break a twig from the nearest tree. The pilgrim obeys the branch snaps and bleeds. ‘Why would you do that to me’, asks the tree. Dante freaks out, of course.

We are in the forest of the suicides. The tree is Pier delle Vigne, or what is left of him.

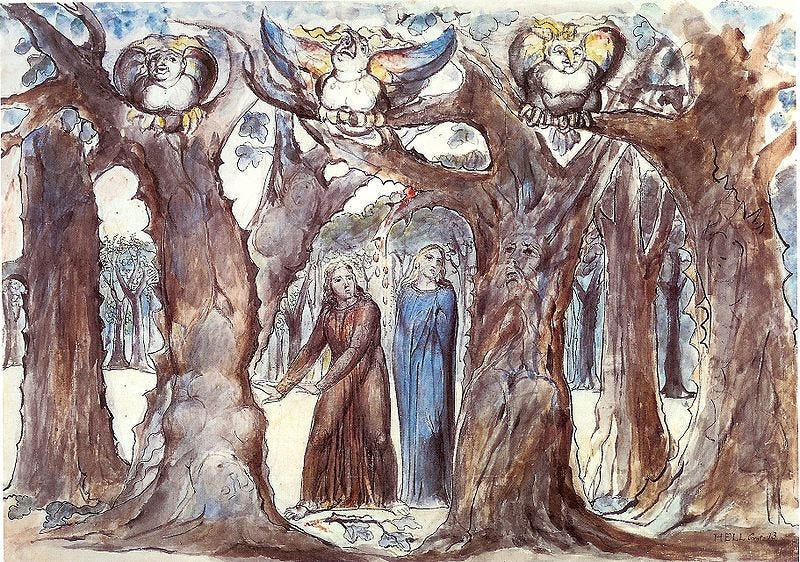

After two rather technical cantos, we come to a deeply personal one. From the bloody river of the homicides, the poets move deeper into the 7th circle and cross into its second ring. Here Dante lingers on the description of the landscape more than in any other canto. We’re told of the darkness of the forest, a “scrubby wilderness so bitter and dense” (v. 7), and of its trees “dismal in colour” (v. 3) and “knotty and entwined” (v. 5). Their twisted branches home the nests of Harpies, beastly creatures with human heads and bodies like birds of prey. To top it all off, a wailing meets the ears from every part, with no visible source to attribute it to.

Virgil, seeing Dante’s confusion, suggests that he break off a little branch from a tree and the nearly 30-verse long descriptive passage suddenly makes sense. The landscape - previously evocative of the sin punished in it - is the sinners.

Dante breaks off a branch from the tree that once was Pier delle Vigne, former chancellor to Frederick II, who killed himself after being unjustly accused of treason by what he believed to be (and most historians agree) a group of conspiring courtiers. The contrapasso here is deceptively simple: those who have violently given up their human existence shall be refused their human bodies and are to live in eternity as inferior forms of life, namely plants.

But at the root (if you’ll excuse the pun) of suicide, there is a greater injury to god. To take one’s own life, according to Christian tradition, is to repudiate the love of God, since it is pure divine love that prompted the creation of humankind.

I will pause here to point out that the image of the bleeding and speaking plant is not novel, but rather lifted from Virgil’s Aeneid. In Book III, Aeneas sails to Thrace and as he arrives, he prepares to offer sacrifices to the gods. As he’s clearing a spot on the beach from weeds and shrubs, he tears at the roots of a bush and sees that blood soaks the earth beneath it. The bush begins to speak and reveals its identity: he is Polydorus, the son of Priam, who has come to Thrace seeking asylum but was betrayed by the Thracian king after the fall of Troy when the latter killed him to ingratiate himself with Agamemnon. There is a direct allusion to this borrowing when Virgil himself apologises to Piero for having told Dante to break off his branch, v. 46-49.

However, Dante takes the image to the next level. First, the single bush-Polydorus has now become a forest spanning an entire ring of hell. Second, the transmutation of people into plants is not as seemingly random as in the Greek myths (there is no specific reason why Polydorus’s blood has grown into a bush like there is no moral teaching behind Daphne’s sad fate. Although, the myth of Narcissus is an exception). Dante’s innovation is that he infuses the mythical with the ethical.

This is not to say he doesn’t have any reservations when it comes to judging Pier delle Vigne. I said above that this is a deeply personal canto. In many ways, critics have read Piero’s character as a stand-in for Dante himself. Both men of letters, both entirely dedicated to politics and civil society, both betrayed by those they loved and served - Piero by Frederick II, Dante by the ruling Florentine classes. Dante’s sympathy for Piero seems to also leave room for debate as to whether there is such a thing as a permissible suicide. Once again, we return to Dante’s background in Greek philosophy, where in certain cases suicide is preferable to dishonour (see the stoics)

Having suffered the humiliation of exile himself, the poet gives Piero room to explain his choice at length. But in the eyes of the Christian god, a sin remains a sin. Piero has no reason to hope for salvation, no matter how noble a character he was in life. Furthermore, he explains, his punishment will carry on through Judgement Day, when, while other souls will be reunited with their bodies, the suicides will remain trees and their carnal shape will hang from their branches in eternity.

But Dante likes Piero and while he can’t do anything about his spiritual afterlife, he can help restore his legacy on earth. Which he does in the only way a poet can - through language. The language and imagery of this canto, particularly of the verses spoken by Pier delle Vigne, is one of my favourite in the Comedy. On the one hand the description of the twisted dark wood that “bore no sign of any path ahead” captures the labyrinthine thinking and inconsolable despair that must plague those driven to suicide. On the other, Piero’s passionate speech, dotted here and there with the most satisfying etymological figures (which I will leave here in Italian, although the Kirkpatrick translation does them reasonable justice), reads almost like a sad song. Verses 64-71 in the Italian text read

La meretrice che mai da l’ospizio

di Cesare non torse li occhi putti,

morte comune e de le corti vizio,

infiammò contra me li animi tutti;

e li ‘nfiammati infiammar sì Augusto…

…L’animo mio, per disdegnoso gusto,

credendo col morir fuggir disdegno,

inguisto fece me contra me giusto.

The language changes when, suddenly, the silence of the first is broken by the wails of two figures who come running, naked and scratched all over, chased by a pack of “bitches” (Dante’s words not mine). These are the souls of the squanderers, people who violently wasted away their fortunes, both material and intellectual/ spiritual. One of them was Lano di Ricolfo Maconi, who according to Dante’s contemporaries spent all his fortune away and then threw himself into the battle of Pieve al Toppo knowing that he was facing sure death, because he didn’t want to live in the poverty he created for himself. The other, Iacopo da Santo Andrea, was said to have set fire to his own property simply because he wanted to see a big fire. What is it with Italians and setting fire to things?

Iacopo tries to hide in a bush, but the dogs find him and tear him to shreds, breaking the branches of the bush in the process. It is the anonymous bush that has the last humble word. He denounces the corruption of Florence which led so many men to suicide, himself among them.