Canto XX and XXI

First of all, sorry there was no Inferno last week - I had some technical difficulties. But fear not - there’s a double newsletter this week, to get us back on track!

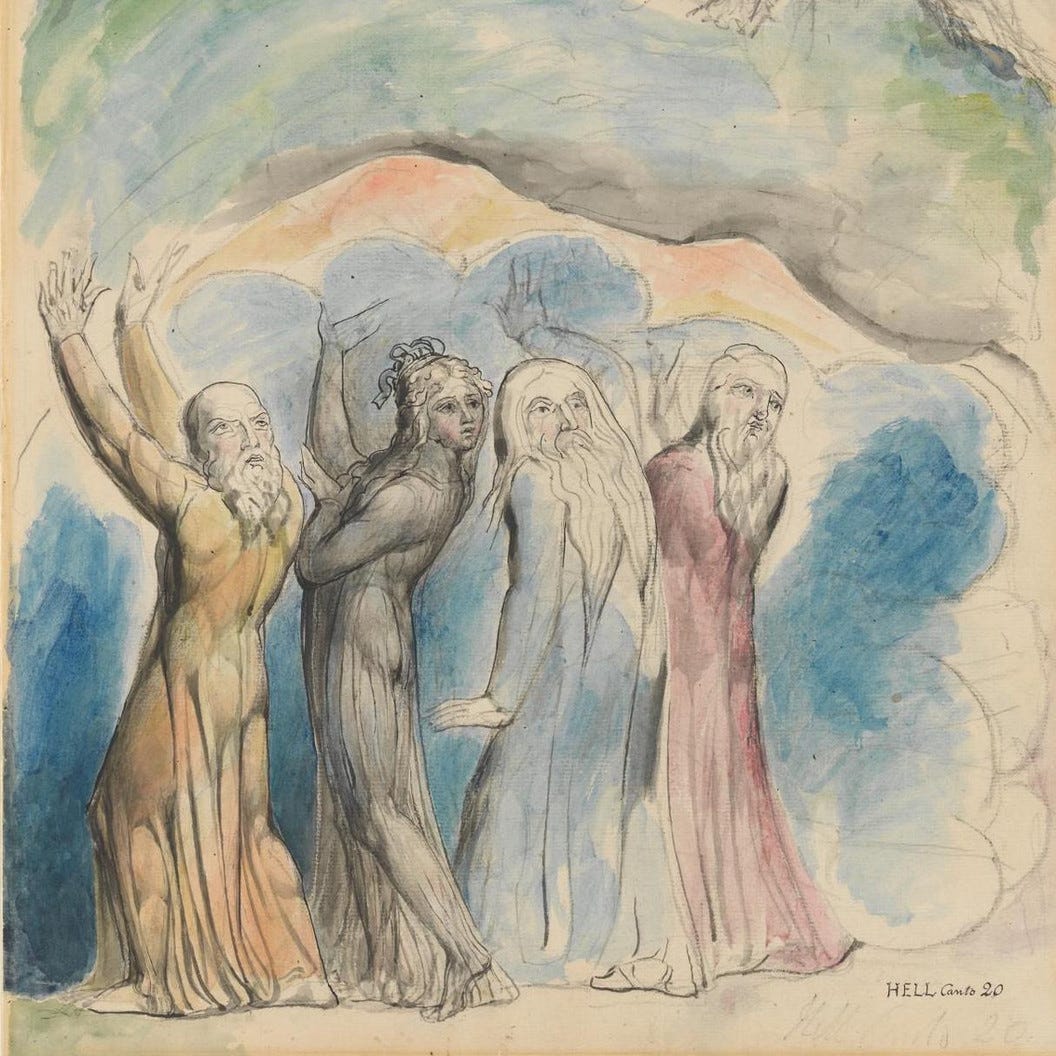

If we could hear canto 19, it would have been loud. Feet were kicking, skin was burning, Dante had a big boy rant. Canto 20, however, is completely silent.

Where in canto 19 the corruption of the human soul made the poet angry, in canto 20 it brings him such inconsolable sadness that he can’t help but weep. Silent crying, in fact, is both the soundtrack and backdrop for the whole canto, as is made clear from the very beginning. We are in the fourth pocket of the 8th circle, a depth described as “washed… with agonizing tears” (v. 6). Here, a crowd of sinners walks round and round in a slow procession, “in silence, weeping - as slow in pace as litanies on earth” (v. 8-9).

The sinners punished here are the soothsayers, people who claimed that they could see the future, be it through magic, astrology, the ability to read omens, or commune with spiritual beings. Their sin is therefore one of deceit since according to Christian belief humans can't tell the future, as well as of arrogance, because it stems from a desire to be God-like (although you could argue that the Christian God doesn’t “know” the future as much as he “decides” it).

Their slow, mournful walk is not their punishment but a consequence of it, Dante realises. The reason why the sinners are so slow is that they’re walking backwards. Or rather, their heads are facing in the right direction, but their necks have been twisted and the rest of their bodies are facing the other way, so they are at the very least stepping backwards, which slows them down. The contrapasso is pretty straightforward: those presumptuous enough to claim that they can see ahead onto the future, shall now forever look backwards, never again able to see before them.

Seeing the human body twisted like this is the last straw for Dante on two narratorial levels: Dante the pilgrim bursts into tears. Dane the poet breaks his narration to address the reader directly:

That God may grant you, as you read, the fruit

that you deserve in reading, think, yourselves:

could I have kept my own face dry, to see,

close by, that image of our human self

so wrenched from true that teardrops from the eyes

ran down to rinse them where the buttock cleave?

So, the sinners are crying and the tears run down their bums, Dante’s crying and looking at their bums - it’s all very quiet and sad.

Seeing this, Virgil, in true Virgil fashion, tells Dante to get a grip. We’ve seen Dante feel empathy for sinners in previous cantos and it never seemed to be a problem for Virgil. Here, however, he points out to Dante that these people are suffering according to God’s will, and there’s nothing more impious than to question it. It could be that he’s had enough of Dante’s mood swings, but I’ve always interpreted this sudden change in attitude as an indication that they are now so far down in hell that they have moved past the point of compassion. He then goes on to name and shame some of the sinners present.

The first thing worthy of note is the sheer volume of them. This is because the divinatory arts were extremely popular both in Dante’s day and the centuries preceding them. Every prince had his own fortuneteller/ spiritual adviser whom they would consult on everything, from personal decisions to political and military matters.

He points out Amphiaraus, one of the leaders of the Seven against Thebes, who was said to have foreseen the death of everyone in battle and tried to desert. Next, he mentions Tiresias, the blind seer of Thebes, best known through Ovid’s telling of his story in the Metamorphoses. In Ovid’s poem, he gets turned into a woman for 7 years after hitting two mating snakes with a stick and wounding them. Next to Tiresias a historical figure, Arruns, an Etruscan prince who was summoned to Rome during the dispute between Caesar and Pompey and was said to have predicted the civil war that would break out between them.

Lastly, a female sinner, Manto, daughter of the aforementioned Tiresias and a witch herself, was said to have fled Thebes after the war and settled in modern-day northern Italy, and founded Virgil’s hometown Mantua. Virgil goes into a lengthy bit of exposition about the origins of Mantua, all meant to disrupt the classical tradition of associating the genesis of a city with a magical event/legend (think Romulus and Remusand the birth of Rome). By going into extenuating (let’s be honest) historical detail about the founding of Mantua, Virgil positions himself against this tradition and leads by example in condemning those who did otherwise.

The canto closes with Dante basically saying, cool, but can you tell me more about these other people? Which Virgil does.

We’re told that Eurypylus is there, a priest who was sent to commune with the god Apollo after the Trojan war and find out when there would be strong enough winds for the Greeks to sail back home. As is Calchas, famous for being Agamemnon’s fortuneteller and overseeing the sacrifice of Iphigenia at the beginning of the Iliad. As they make their way to the next pocket we’re given one last name, that of Guido Bonatti, famous astrologer and adviser to a series of political figures who lived just before Dante and whose work and personal history the poet was probably very well acquainted with.

But I think the glaring takeaway from this whole canto is modern-day astrology girlies deserve justice. Not only was astrology regarded as a serious discipline for centuries, but it was a tool that MEN with little talent beyond manipulation used to con rich people out of money. So everyone go to your local tiktok astrology girl and apologise.

Canto 21 is hilarious. One of my absolute favourites, it completely breaks with the rest of the Comedy in subject matter and tone. The few sinners present are more props than actors and we get to have a close look at the most underrated and arguably coolest inhabitants of hell - the demons. Most critics see canto 21 (and 22, to some degree) as a moment of comic relief - the linguistic register is the lowest we’ve seen so far, there are no important people giving important speeches and the closing verse tells us that one of the demons farts.

Other critics have argued that, actually, the humour is not lighthearted at all. The sinners punished in this pocket of the 8th circle are the grafters (or corrupted officials) and this is the very crime used as a pretext in Dante’s exile from Florence. The tone, then, is not comical at all but tragic.

Personally, I see strong autobiographical brushstrokes all throughout the canto, but I also see humour. I think Dante saw these accusations so insultingly below him that this comical language full of echoes of the farcical plays of the time is the only way he would dignify addressing them.

The canto begins with a description of the landscape delivered through a running similitude that goes on for about a dozen verses. Dante and Virgil have entered the 5th pocket of the 8th circle via a bridge. Below them is a pool of boiling black tar, like the one in the Arsenal or shipyard of the Venetian empire. The tar was used to insulate the boats that had been on the water all summer to get them ready for the following season, and since this work was carried out in winter, this huge vat was constantly kept boiling to prevent the tar from solidifying. I know what you’re thinking: nautical imagery a the beginning of a canto? Groundbreaking.

As Dante takes in this view, Virgil calls out to him to watch out. A “black demon” is charging right at them. The verses describing him are some of the most vivid in the poem

How ferocious all his features looked.

How viciously his every move seemed etched,

wings wide apart, so lithe and light of foot.

The hunch blades of his shoulders, keen and proud,

bore up the haunches of some criminal,

his hook fixed firm in tendons at each heel.

Mounting our bridge, demonically he barked

So, dark as the tar they sink the sinners in, winged but not specified if able to fly (perhaps an ability they lost when fallen from heaven?), the demons carry sinners suspended on hooks by their feet and quickly throw them in the tar before going back up to collect more.

In the exchange of words between demons and demons at sinners, it is made clear that this pocket is full of “lucchesi”, meaning people from the city of Lucca, which at the time was the main camp of the Black Guelphs, the opposing political to Dante (you will remember he was a White Guelph). That the people who accused him of barratry are the ones in the section of hell that punishes that very crime adds to the comical aspect of the canto. At the time of writing, Dante had lived in exile for at least 15 years. This is not to say he’s over it - and the theme of exile is dealt with very seriously elsewhere in the poem - but he’s clearly at the point where he can poke fun at it. This is reflected in the farcical description of the job of the demons who supervise the pool of tar, which is to make sure that the sinners stay submerged. Whenever one of them pokes their head above the surface, the demon proceeds to poke them with their comically large fork, like a cook stirring a dish that has been brought to a boil.

The demons see Dante and Virgil and all gather in the middle of the bridge to stop them. A scene we’ve seen before at the gate of the city of Dis. Except, this time Virgil goes and talks with the leader of the devils, Rottentail, and secures safe passage. This sets up another hilarious scene where has to walk among the other demons and overhears them whispering about the things they want to do to him.

But Virgil’s authority is absolute and the demons not only let them through but offer to show them a different path, as the bridge they were on had collapsed “a thousand years, two centuries and sixty-six” before. This date refers to the death of Christ when, according to Christian tradition, Mount Golgotha shook in horror along with the rest of creation.

The canto closes with the aforementioned fart. In a parody of the military life, Rottentail is said to have ordered the other demons to fall in line and leave Dante alone by “making a trumpet of his arse”. Poetic stuff.